Inclusive Facilitation & Data Discovery

Overview

Under Construction

Learning Objectives

TBD

Preparation

TBD

Benefits of Enabling Full Participation

Creating the conditions for all team members to feel welcome and able to fully participate advances diversity, equity, and inclusion in science. As we learned in the Team Science Practices module it also has instrumental benefits, as diverse teams have been shown to be more productive and to produce higher impact results than less diverse teams. In part, that productivity can be attributed to the ability of the group to elicit and work with novel ideas and approaches, allowing more innovative analysis and problem solving.

Facilitating equitable participation also helps to unleash the full capacity of a team to get things done. Too often, potential contributors opt out of offering their skills and talents to a collaborative endeavor because they feel undervalued or unclear on how to contribute. It might not feel worth their time to try to assert an idea or opinion when it doesn’t feel welcome. A process that creates opportunities for everyone to engage and feel included can help avoid this situation.

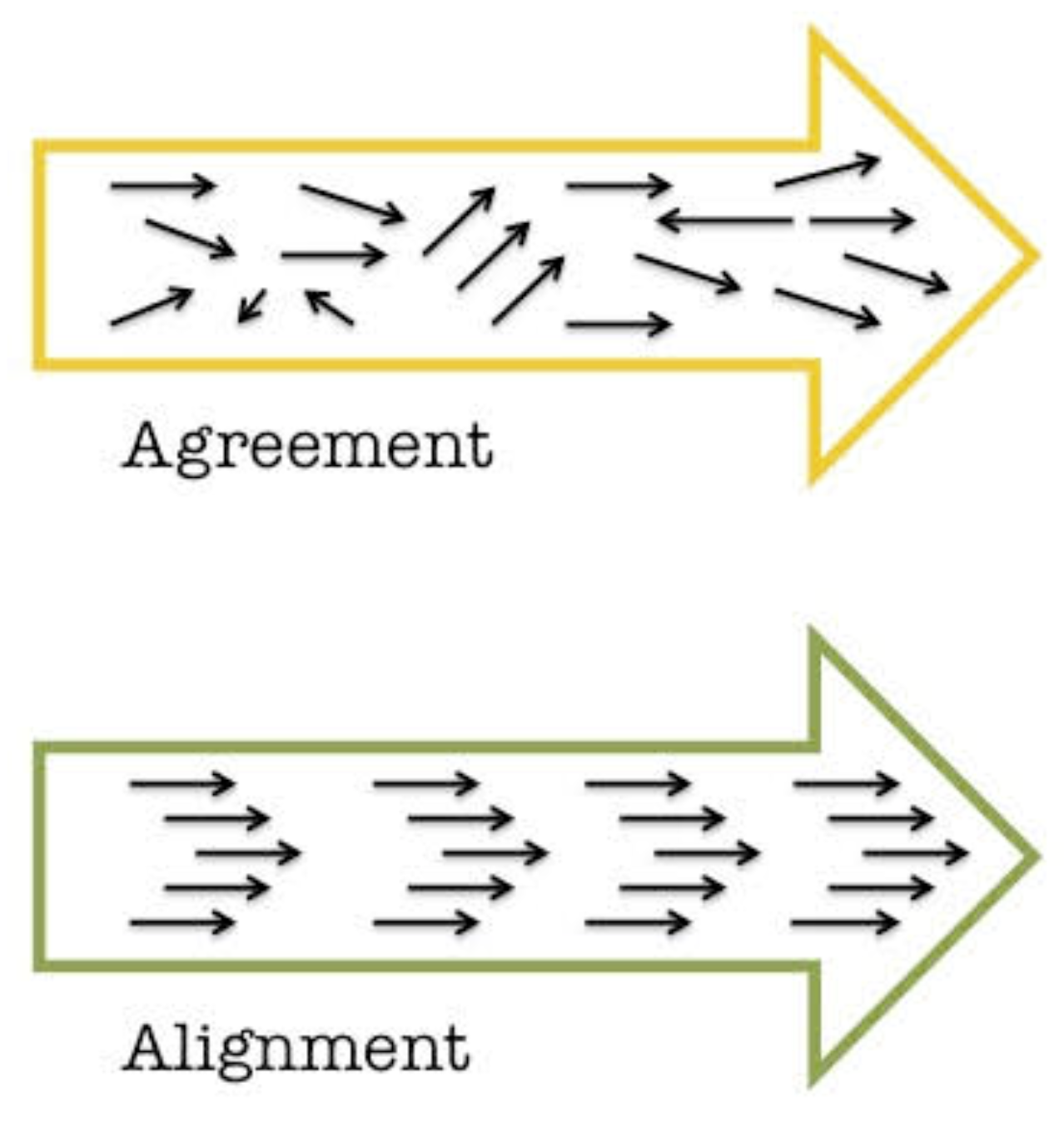

Finally, when the time comes for decision making, effective facilitation can ensure that the full range of questions, opinions, and concerns has been surfaced and weighed before the group makes a decision. This is critical. If you move forward with surface-level agreement, but without true alignment, commitment to the decision is likely to erode over time.

Moving from Debate to Dialogue

Dialogue is a collaborative effort to understand and learn from each other. Debate, on the other hand, is an oppositional effort to convince the other side that you are right. Inclusive facilitation aims to support dialogue and skillful discussion. Dialogue allows groups to recognize the limits on their own and others’ individual perspectives and to strive for more coherent thought. Dialogue becomes a container for collective thinking and exploration - a process that can take teams in directions not imagined or planned. In dialogue, all views are treated as equally valid, and different views are presented as a means toward discovering a new view. Participants listen to understand one another, not to win. Complex issues are explored and shared meaning is created. When it comes time to make a decision, skillful discussion is required. Both skillful discussion and dialogue are critical to the collaborative process, and the more artfully a group can move between these two forms of discourse (and out of less productive debate and polite discussion) according to what is needed, the more effective the group will be.

- Intent to win

- Listening to be understood

- Power struggles

- Competition “turf war”

- Loudest wins

- Ideas judged by who says them

- Intent to protect self, others

- Surface friendly

- Ideas judged by friendships/relationships

- Impulsive, based on feeling, low data

- Influence occurs outside the meeting

- Limited active or empathetic listening

- Intent is closure; informed decisions

- Balance influence and inquiry

- Focus on issues not personalities

- Reasoning is made explicit

- Ask about assumptions without criticizing

- Influence is based in logic and data

- Intent to build mutual understanding

- Listening to understand thoughts and feelings

- Able to suspend assumptions

- Energy used to find the right questions

- “Container” for collective thinking

- Influence is found in shared meaning created by groups

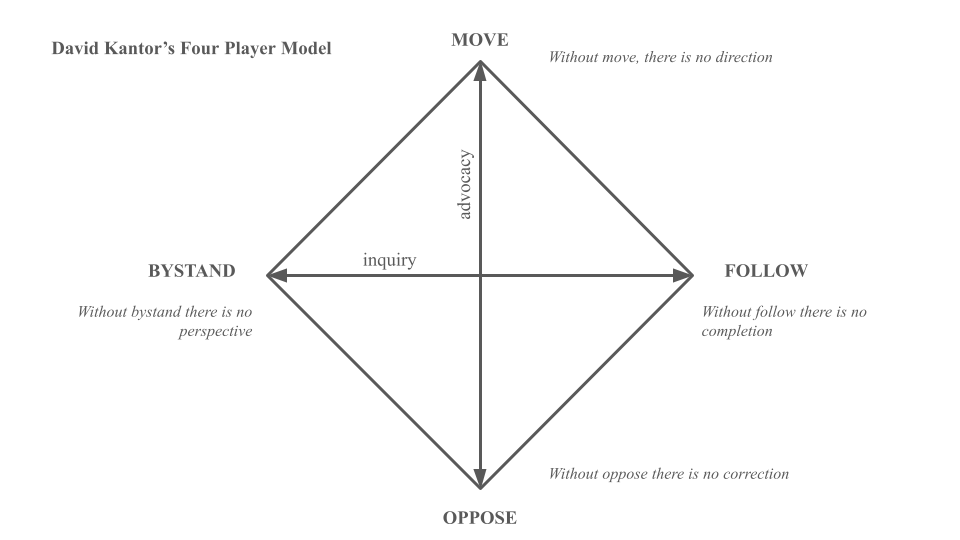

David Kantor’s Four Player Model is a helpful tool for diagnosing “stuck” patterns of communication, (including entrenched debate and polite discussion), and interceding to help shift to a more productive pattern.

Based on over 30 years of observation and study of face-to-face communication in many groups, Kantor developed the Four Player Model and a broader theory of Structural Dynamics. The model identifies four actions of effective communication:

- Move - Initiate an idea, action, or direction for conversation

- Follow - Continue the direction or flow of the conversation; support a move, either by agreeing or asking for more information

- Oppose - Challenge or disagree with the idea, action, or suggested direction

- Bystand - Notice and articulate what’s happening in the conversation, add a neutral perspective

Each action in a group conversation can be coded into one of these four action modes. Most of us have one of these modes that we feel most comfortable in and tend to default to in a group. The most effective conversations involve good listening and the skillful use of all four modes. Common “stuck” patterns emerge when groups are not deploying all four actions.

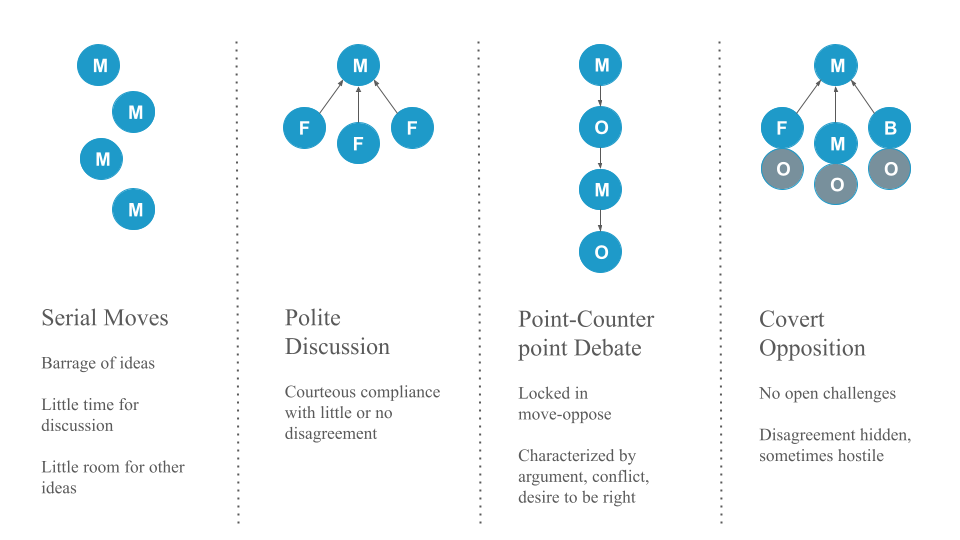

Lots of idea generation; may feel like a barrage; no clear thread, decision, or follow through

Any of the other modes can help here, since move is the only mode being engaged.

Add a follow to give momentum to a particular move and steer the conversation in that direction, e.g., “Can we go back to the idea that Jose put on the table? That felt like a topic that could really use our attention. Shall we focus there?”

Offer an effective oppose - “We’ve heard a lot of different ideas. I’d like to focus on the one Amelia laid out. I’m interested in the research question, but I don’t think machine learning is going to be the most productive approach. Can we dig in to this one?”

Use a bystand to bring awareness to and disrupt the dynamic - “Hey gang, we’re 20 minutes into our call and we’ve put a lot of different topics on the table. Where do we want to focus ourselves so we can walk away with some clear next steps?”

Moves are followed with little discussion or resistance; also known as Courteous Compliance

Prompt an effective oppose:

- Who sees it differently?

- What’s at risk here?

- What other angles should we consider?

Invite a bystand:

- Where is the group right now?

- What are you noticing?

- Is there an elephant in the room that needs to be named?

Individuals are locked in a back and forth where each move is met with resistance / opposition

Invite a follow:

- What do you like about the proposal on the table?

- What do you agree with that we could build upon?

Coach for a more effective oppose by inviting those who have been opposing to identify some aspect of the idea they do agree with (even if only 2%), in addition to the specific aspects they object to.

Invite a bystand:

- In addition to the two viewpoints on the table, I’d love to hear from some other perspectives.

- What are you noticing?

- What might we be missing?

On the surface, moves are followed, and the conversation appears harmonious, but below the surface, people have unspoken reservations. Opposition tends to be expressed outside the bounds of the conversation or harbored as resentment.

Uneven power dynamics are often behind this pattern - group members defer to the moves of those with more power or seniority.

Invite those with more power to experiment with following or bystanding to open up space for other players to make a move.

Prompt a transparent oppose:

- Who sees it differently?

- What’s at risk here?

- Are there some cons to the proposed idea?

If others aren’t comfortable, you can offer an oppose, e.g., by suggesting the limits of the proposed move be tested across different scenarios.

Offer a bystand, e.g., “I want to offer a reflection from another team I was part of. On that team, we kept having meetings where it seemed like everyone was in agreement, but then we would leave, and over and over again there would be little follow through and more than a little grousing. People’s real opinions were only coming out in side conversations outside of the meeting. We lost a lot of time and forward momentum because people didn’t feel like they could air their concerns in the larger group. Do you see that happening here? Does anyone have a suggestion for how to make this a safer space to critically discuss ideas?”

Designing Meetings for All Thinking Styles

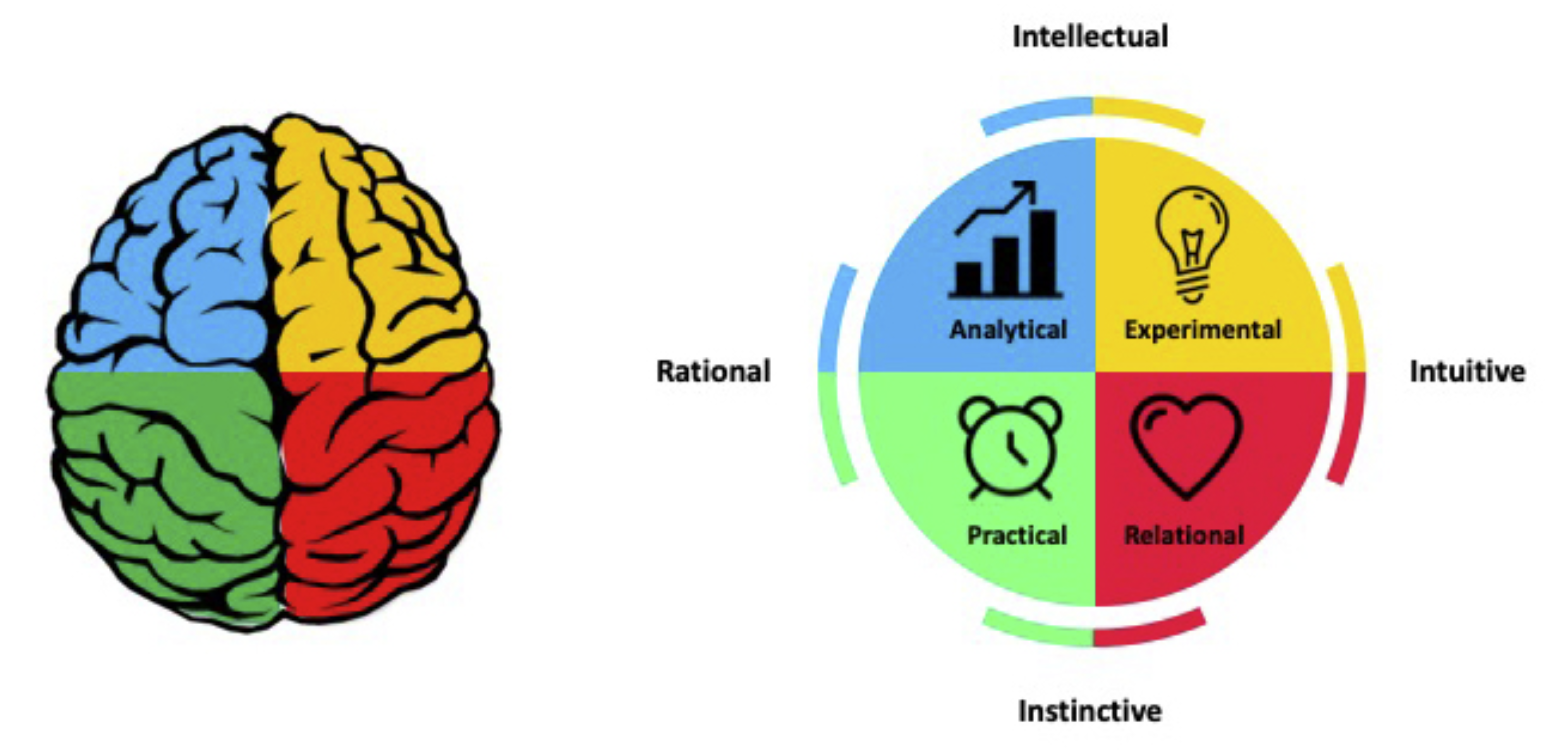

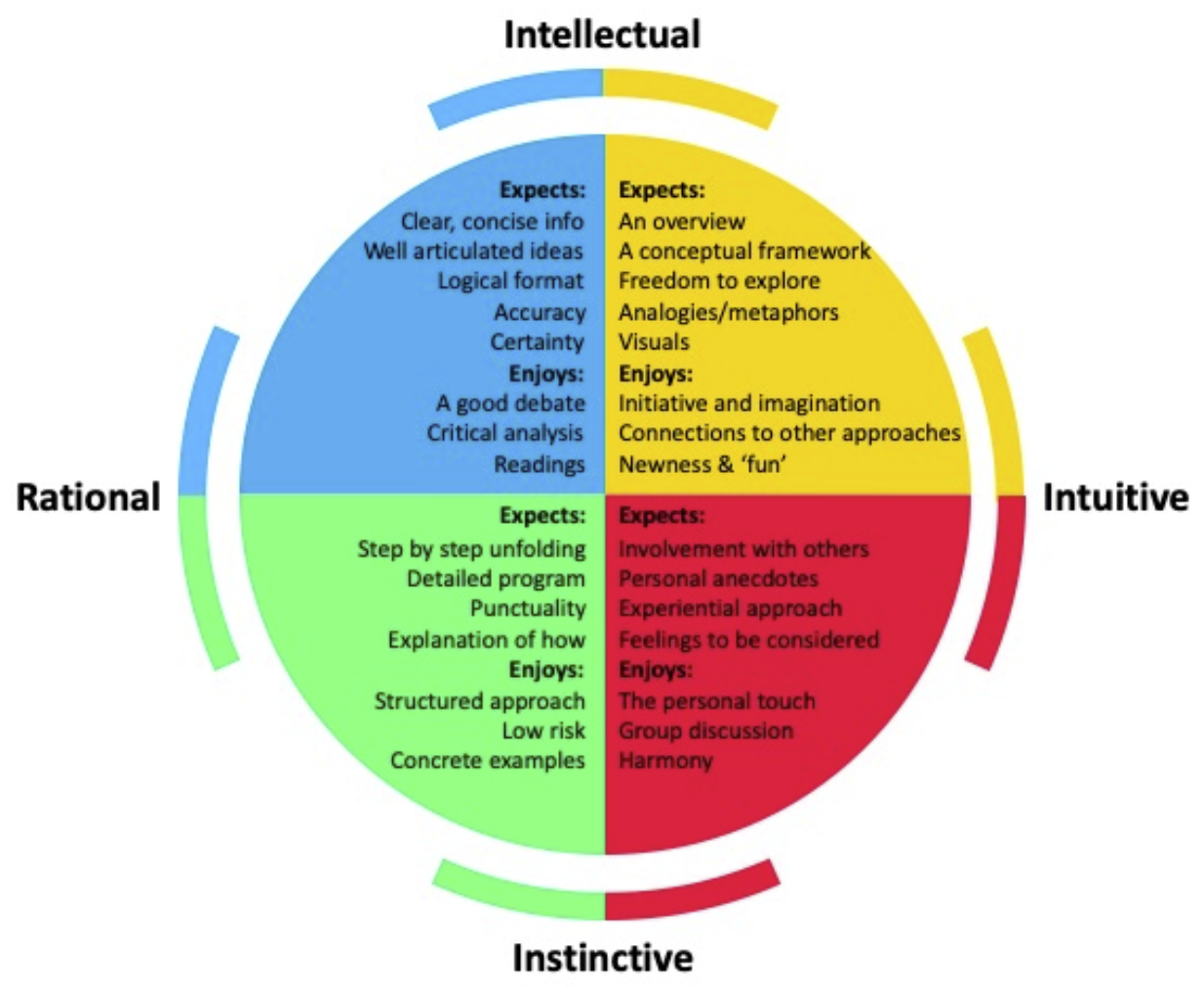

People have different thinking preferences which influence what they expect and enjoy in group processes (see Ned Herrmann’s Whole Brain Model below).

Ensuring Equitable Access to Participation

To tap diverse perspectives and catalyze productivity and creative problem-solving, we need to design meetings (and projects) so everyone can participate fully, rather than just a few. When tackling complex challenges, voices from the edge are often critical to uncovering new insights and approaches. Democratizing participation doesn’t have to be all about controlling the dominant voices in a group; with thoughtful planning and some simple tools, you can design any conversation so that everyone can contribute.

A few simple techniques can help:

- Mix up the format, e.g., combining silent reflection, round robin, breakout groups, plenary, and/or “liberating structures” (more on these below)

- Offer different channels for information sharing - verbal, nonverbal, written, visual, informal, formal

- Track and stack who wants to speak

- Invite, amplify, and credit “quieter” voices

- Use active listening - reflect back what you think you are hearing in simple terms and check your assumptions regularly

Be creative and empathetic when you design your agenda. Think about your participants and what is going to help all of them participate fully and creatively. Beyond the thinking preferences, you may also want to consider these other dimensions of diversity when planning your process design and facilitation:

- Introverts vs. extroverts

- Visual, auditory and kinesthetic learners

- Disciplinary diversity

- Career stage

- Language

- Time zone (for geographically distributed teams)

Data Repositories

There are a lot of specialized data repositories out there. These organizations are either primarily dedicated to storing and managing data or those operations constitute a substantive proportion of their efforts. In synthesis work, you may already have some datasets in-hand at the outset but it likely that you will need to find more data to test your hypotheses. Data repositories are a great way of finding/accessing data that are relevant to your questions.

You’ll become familiar with many of these when you need a particular type of data and go searching for it but to help speed you along, see the list below for a non-exhaustive set of some that have proved useful to other synthesis projects in the past. They are in alphabetical order. If the “ Package” column contains the GitHub logo () then the package is available on GitHub but is not available on CRAN (or not available at time of writing).

| Name | Description | Package |

|---|---|---|

| AmeriFlux | Provides data on carbon, water, and energy fluxes in ecosystems across the Americas, aiding in climate change and carbon cycle research. | amerifluxr |

| DataONE | Aggregates environmental and ecological data from global sources, focusing on biodiversity, climate, and ecosystem research. | dataone |

| EDI | Contains a wide range of ecological and environmental datasets, including long-term observational data, experimental results, and field studies from diverse ecosystems. | EDIutils |

| EES-DIVE | The Environmental System Science Data Infrastructure for a Virtual Ecosystem (ESS-DIVE) includes a variety of observational, experimental, modeling and other data products from a wide range of ecological and urban systems. | – |

| GBIF | The Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) aggregates global species occurrence data and biodiversity records, supporting research in species distribution and conservation. | rgbif |

| Google Earth Engine | Google Earth Engine is a cloud-based geospatial analysis platform that provides access to vast amounts of satellite imagery and environmental data for monitoring and understanding changes in the Earth’s surface. | rgee |

| Microsoft Planetary Computer | The Microsoft Planetary Computer is a cloud-based platform that combines global environmental datasets with advanced analytical tools to support sustainability and ecological research. | rstac |

| NASA | Provides data on earth science, space exploration, and climate, including satellite imagery and observational data for both terrestrial and extraterrestrial studies. Nice GUI-based data download via AppEEARS. | nasadata |

| NCBI | Hosts genomic and biological data, including DNA, RNA, and protein sequences, supporting genomics and molecular biology research. | rentrez |

| NEON | Provides ecological data from U.S. field sites, covering biodiversity, ecosystems, and environmental changes, supporting large-scale ecological research. | neonUtilities |

| NOAA | Offers meteorological, oceanographic, and climate data, essential for understanding atmospheric conditions, marine environments, and long-term climate trends. | EpiNOAA-R |

| Open Traits Network | While not a repository per se, the Open Traits Network has compiled an extensive lists of repositories for trait data. Check out their repository inventory for trait data | – |

| USGS | Hosts data on geology, hydrology, biology, and geography, including topographical maps and natural resource assessments. | dataRetrieval |

Searching for Data

If you don’t find what you’re looking for in a particular data repository (or want to look for data not included in one of those platforms), you might want to consider a broader search. For instance, Google is a surprisingly good resource for finding data and–for those familiar with Google Scholar for peer reviewed literature-specific Googling–there is a dataset-specific variant of Google called Google Dataset Search.

Search Operators

Virtually all search engines support “operators” to create more effective queries (i.e., search parameters). If you don’t use operators, most systems will just return results that have any of the words in your search which is non-ideal, especially when you’re looking for very specific criteria in candidate datasets.

See the tabs below for some useful operators that might help narrow your dataset search even when using more general platforms.

Use quotation marks ("") to search for an exact phrase. This is particularly useful when you need specific data points or exact wording.

Example: "reef biodiversity"

Use an asterisk (*) to search using a placeholder for any word or phrase in the query. This is useful for finding variations of a term.

Example: Pinus * data

Use a plus sign (+) to search using more than one query at the same time. This is useful when you need combinations of criteria to be met.

Example: bat + cactus

Use the ‘or’ operator (OR) operator to search for either one term or another. It broadens your search to include multiple terms.

Example: "prairie pollinator" OR "grassland pollinator"

Use a minus sign (-; a.k.a. “hyphen”) to exclude certain words from your search. Useful to filter out irrelevant results.

Example: marine biodiversity data -fishery

Use the site operator (site:) to search within a specific website or domain. This is helpful when you’re looking for data from a particular source.

Example: site:.gov bird data

Use the file type operator (filetype:) to search for data with a specific file extension. Useful to make sure the data you find is already in a format you can interact with.

Example: filetype:tif precipitation data

Use the ‘in title’ operator (intitle:) to search for pages that have a specific word in the title. This can narrow down your results to more relevant pages.

Example: intitle:"lithology"

Use the ‘in URL’ operator (inurl:) to search for pages that have a specific word in the URL. This can help locate data repositories or specific datasets.

Example: inurl:data soil chemistry