Reproducible Work & Navigating Conflict

Overview

Under Construction

Learning Objectives

TBD

Preparation

TBD

Reproducible Coding

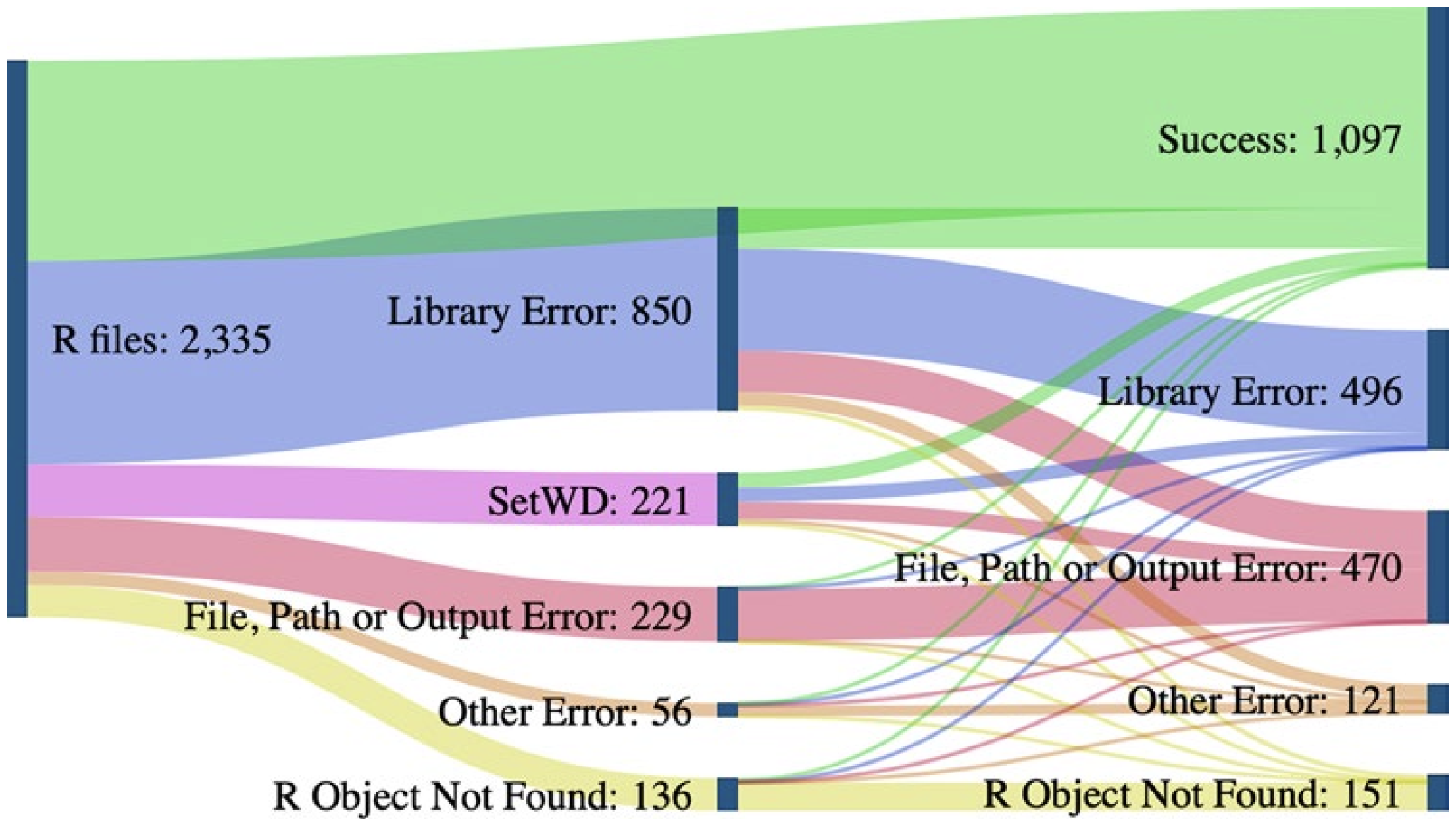

Now that you’ve organized your project in a reasonable way and documented those choices, we can move on to principles of reproducible coding! Doing your data operations with scripts is more reproducible than doing those operations without a programming language (i.e., with Microsoft Excel, Google Sheets, etc.). However, scripts are often written in a way that is not reproducible. A recent study aiming to run 2,000 project’s worth of R code found that 74% of the associated R files failed to complete without error (Trisovic et al. 2022). Many of those errors involve coding practices that hinder reproducibility but are easily preventable by the original code authors.

When your scripts are clear and reproducibly-written you will reap the following benefits:

- Returning to your code after having set it down for weeks/months is much simpler

- Collaborating with team members requires less verbal explanation

- Sharing methods for external result validation is more straightforward

- In cases where you’re developing a novel method or workflow, structuring your code in this way will increase the odds that someone outside of your team will adopt your strategy

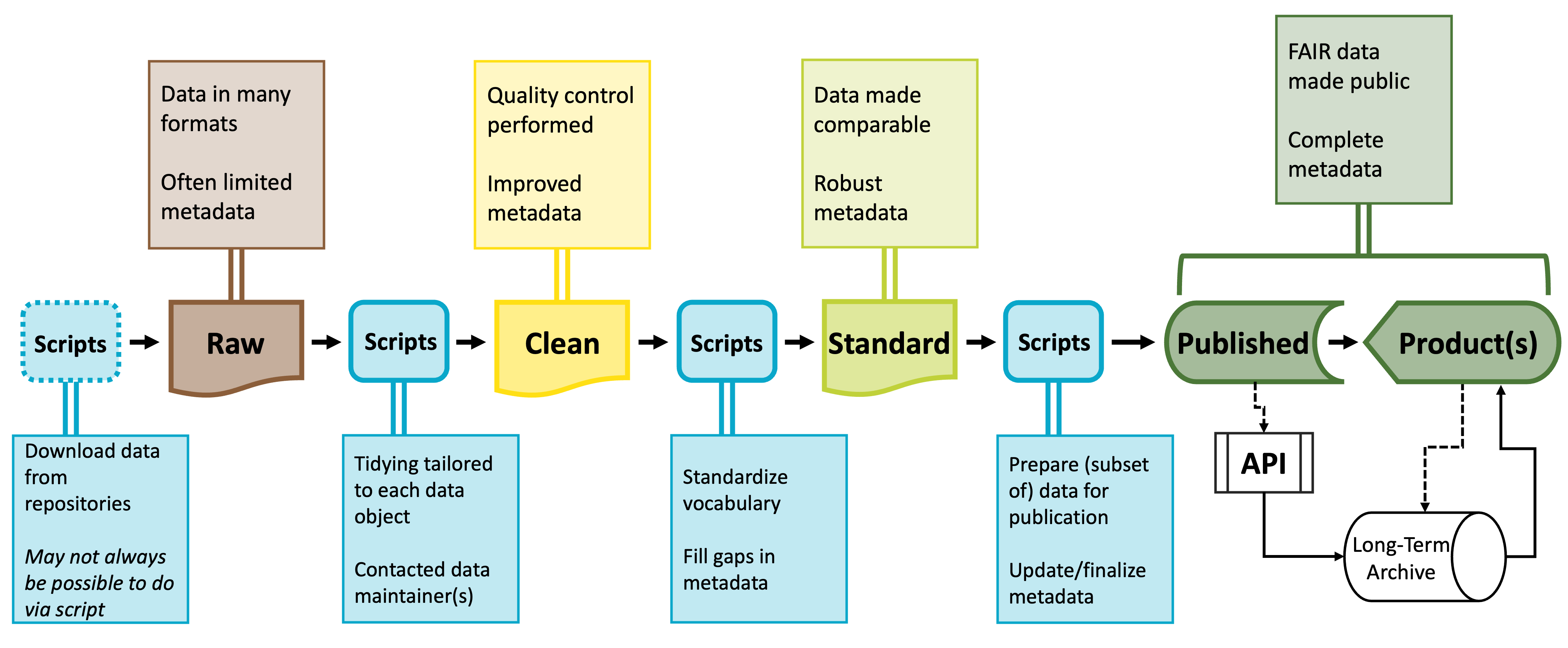

Code and the Stages of Data

You’ll likely need a number of scripts to accomplish the different stages of preparing a synthesized dataset. All of these scripts together are often called a “workflow.” Each script will meet a specific need and its outputs will be the inputs of the next script. These intermediary data products are sometimes useful in and of themselves and tend to occur and predictable points that exist in most code workflows.

Raw data will be parsed into cleaned data–often using idiosyncratic or dataset-specific scripts–which is then processed into standardized data which can then be further parsed into published data products. Because this process results in potentially many scripts, coding reproducibly is vital to making this workflow intuitive and easy to maintain.

You don’t necessarily need to follow all of the guidelines described below but in general, the more of these guidelines you follow the easier it will be to make needed edits, onboard new team members, maintain the workflow in the long term, and generally maximize the value of your work to yourself and others!

Packages, Namespacing, and Software Versions

An under-appreciated facet of reproducible coding is a record of what code packages are used in a particular script and the version number of those packages. Packages evolve over time and code that worked when using one version of a given package may not work for future versions of that same package. Perpetually updating your code to work with the latest package versions is not sustainable but recording key information can help users set up the code environment that does work for your project.

Load Libraries Explicitly

It is important to load libraries at the start of every script. In some languages (like Python) this step is required but in others (like R) this step is technically “optional” but disastrous to skip. It is safe to skip including the installation step in your code because the library step should tell code-literate users which packages they need to install.

For instance you might begin each script with something like:

# Load needed libraries

library(dplyr); library(magrittr); library(ggplot2)

# Get to actual work

. . .In R the semicolon allows you to put multiple code operations in the same line of the script. Listing the needed libraries in this way cuts down on the number of lines while still being precise about which packages are needed in the script.

If you are feeling generous you could use the librarian R package to install packages that are not yet installed and simultaneously load all needed libraries. Note that users would still need to install librarian itself but this at least limits possible errors to one location. This is done like so:

# Load `librarian` package

library(librarian)

# Install missing packages and load needed libraries

shelf(dplyr, magrittr, ggplot2)

# Get to actual work

. . .Function Namespacing

It is also strongly recommended to “namespace” functions everywhere you use them. In R this is technically optional but it is a really good practice to adopt, particularly for functions that may appear in multiple packages with the same name but do very different operations depending on their source. In R the ‘namespacing operator’ is two colons.

# Use the `mutate` function from the `dplyr` package

dplyr::mutate(. . .)An ancillary benefit of namespacing is that namespaced functions don’t need to have their respective libraries loaded. Still good practice to load the library though!

Package Versions

While working on a project you should use the latest version of every needed package. However, as you prepare to publish or otherwise publicize your code, you’ll need to record package versions. R provides the sessionInfo function (from the utils package included in “base” R) which neatly summarizes some high level facets of your code environment. Note that for this method to work you’ll need to actually run the library-loading steps of your scripts.

For more in-depth records of package versions and environment preservation–in R–you might also consider the renv package or the packrat package.

Script Organization

Every change to the data between the initial raw data and the finished product should be scripted. The ideal would be that you could hand someone your code and the starting data and have them be able to perfectly retrace your steps. This is not possible if you make unscripted modifications to the data at any point!

You may wish to break your scripted workflow into separate, modular files for ease of maintenance and/or revision. This is a good practice so long as each file fits clearly into a logical/thematic group (e.g., data cleaning versus analysis).

File Paths

When importing inputs or exporting outputs we need to specify “file paths”. These are the set of folders between where your project is ‘looking’ and where the input/output should come from/go. The figure from Trisovic et al. (2022) shows that file path and working directory errors are a substantial barrier to code that can be re-run in clean coding environments. Consider the following ways of specifying file paths from least to most reproducible.

Absolute Paths

The worst way of specifying a file path is to use the “absolute” file path. This is the path from the root of your computer to a given file. There are many issues here but the primary one is that absolute paths only work for one computer! Given that only one person can even run lines of code that use absolute paths, it’s not really worth specifying the other issues.

Example

# Read in bee community data

my_df <- read.csv(file = "~/Users/lyon/Documents/Grad School/Thesis (Chapter 1)/Data/bees.csv")Manually Setting the Working Directory

Marginally better than using the absolute path is to set the working directory to some location. This may look neater than the absolute path option but it actually has the same point of failure: Both methods only work for one computer!

Example

# Set working directory

setwd(dir = "~/Users/lyon/Documents/Grad School/Thesis (Chapter 1)")

# Read in bee community data

my_df <- read.csv(file = "Data/bees.csv")Relative Paths

Instead of using absolute paths or manually setting the working directory you can use “relative” file paths! Relative paths assume all project content lives in the same folder.

This is a safe assumption because it is the most fundamental tenet of reproducible project organization! The strength of relative paths is actually a serious contributing factor for why it is good practice to use a single folder.

Example

# Read in bee community data

my_df <- read.csv(file = "Data/bees.csv")- 1

- Parts of file path specific to each user are automatically recognized by the computer

Operating System-Flexible Relative Paths

The “better” example is nice but has a serious limitation: it hard coded the type of slash between file path elements. This means that only computers of the same operating system as the code author could run that line.

We can use functions to automatically detect and insert the correct slashes though!

Example

# Read in bee community data

my_df <- read.csv(file = file.path("Data", "bees.csv"))Code Style

When it comes to code style, the same ‘rule of thumb’ applies here that applied to project organization: virtually any system will work so long as you (and your team) are consistent! That said, there are a few principles worth adopting if you have not already done so.

Use concise and descriptive object names

It can be difficult to balance these two imperatives but short object names are easier to re-type and visually track through a script. Descriptive object names on the other hand are useful because they help orient people reading the script to what the object contains.

Don’t be afraid of empty space!

Scripts are free to write regardless of the number of lines so do not feel as though there is a strict character limit you need to keep in mind. Cramped code is difficult to read and thus can be challenging to share with others or debug on your own. Inserting an empty line between coding lines can help break up sections of code and putting spaces before and after operators can make reading single lines much simpler.

Code Comments

A “comment” in a script is a human readable, non-coding line that helps give context for the code. In R (and Python), comment lines start with a hashtag (#). Including comments is a low effort way of both (A) creating internal documentation for the script and (B) increasing the reproducibility of the script. It is difficult to include “too many” comments, so when in doubt: add more comments!

There are two major strategies for comments and either or both might make sense for your project.

“What” Comments

Comments describe what the code is doing.

- Benefits: allows team members to understand workflow without code literacy

- Risks: rationale for code not explicit

# Remove all pine trees from dataset

no_pine_df <- dplyr::filter(full_df, genus != "Pinus")“Why” Comments

Comments describe rationale and/or context for code.

- Benefits: built-in documentation for team decisions

- Risks: assumes everyone can read code

# Cone-bearing plants are not comparable with other plants in dataset

no_pine_df <- dplyr::filter(full_df, genus != "Pinus")Consider Custom Functions

In most cases, duplicating code is not good practice. Such duplication risks introducing a typo in one copy but not the others. Additionally, if a decision is made later on that requires updating this section of code, you must remember to update each copy separately.

Instead of taking this copy/paste approach, you could consider writing a “custom” function that fits your purposes. All instances where you would have copied the code now invoke this same function. Any error is easily tracked to the single copy of the function and changes to that step of the workflow can be accomplished in a centralized location.

Function Recommendations

We have the following ‘rules of thumb’ for custom function use:

- If a given operation is duplicated 3 or more times within a project, write a custom function

Functions written in this case can be extremely specific and–though documentation is always a good idea–can be a little lighter on documentation. Note that the reason you can reduce the emphasis on documentation is only because of the assumption that you won’t be sharing the function widely. If you do decide the function could be widely valuable you would need to add the needed documentation post hoc.

- Write functions defensively

When you write custom functions, it is really valuable to take the time to write them defensively. In this context, “defensively” means that you anticipate likely errors and write your own informative/human readable error messages. Let’s consider a simplified version of a function from the ltertools R package for calculating the coefficient of variation (CV).

The coefficient of variation is equal to the standard deviation divided by the mean. Fortunately, R provides functions for calculating both of these already and both expect numeric vectors. If either of those functions is given a non-number you get the following warning message: “In mean.default(x =”…“) : argument is not numeric or logical: returning NA”.

Someone with experience in R may be able to interpret this error but for many users this error message is completely opaque. In the function included below however we can see that there is a simpler, more human readable version of the error message and the function is stopped before it can ever reach the part of the code that would throw the warning message included above.

cv <- function(x){

# Error out if x is not numeric

if(is.numeric(x) != TRUE)

stop("`x` must be numeric")

# Calculate CV

sd(x = x) / mean(x = x)The key to defensive programming is to try to get functions to fail fast and fail informatively as soon as a problem is detected! This is easier to debug and understand for coders with a range of coding expertise and–for complex functions–can save a ton of useless processing time when failure is guaranteed at a later step.

- If a given operation is duplicated 3 or more times across projects, consider creating an R package

Creating an R package can definitely seem like a daunting task but duplication across projects carries the same weaknesses of excessive duplication within a project. However, when duplication is across projects, not even writing a custom function saves you because you need to duplicate that function’s script for each project that needs the tool.

Hadley Wickham and Jenny Bryan have written a free digital book on this subject that demystifies a lot of this process and may make you feel more confident to create your own R package if/when one is needed.

If you do take this path, you can simply install your package as you would any other in order to have access to the operations rather than creating duplicates by hand.

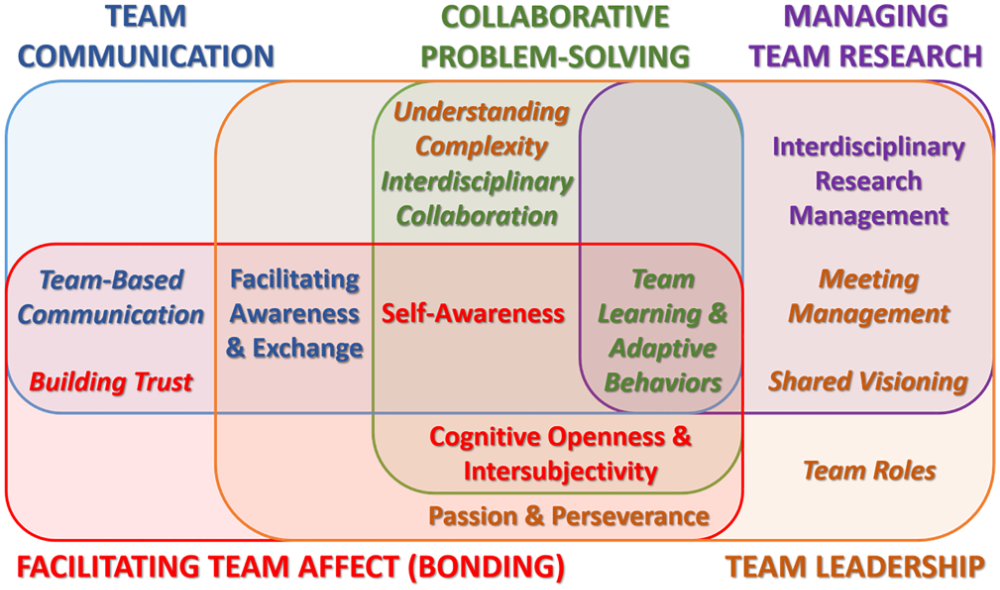

Conditions and Practices that Support Team Functioning

In order for the above mechanisms to operate, teams need to cultivate conditions that encourage all members to contribute at the times and in the ways that they are most skilled and effective. Explore the tabs below for some of these conditions.

Cultivate a learning goal orientation rather than a product goal orientation. Expect to learn from one another and adapt your expectations and plans (Nederveen et al. 2013)

Remain open to revising assumptions and world views. When divergent positions are met only with resistance, groupthink gains the upper hand

Cognitive trust is the rational belief that group members can and will deliver on their portion of the work. When it isn’t present, group members tend to pull back on their own contributions. Good coordination supports cognitive trust by providing clarity and accountability about who agreed to do what work and whether they delivered. It ensures that contributions can be appropriately credited and that work isn’t unnecessarily duplicated. Effective coordination and facilitation make space for all group members to engage.

- Fast and slow processors can be accommodated by making space for written as well as verbal contributions and allowing “thinking time” before expecting a response.

- Visual, auditory and kinesthetic learners take in information (and are more or less fluent) in different formats. Try to provide key information (and allow input) in more than one format.

- Those with caregiving responsibilities may have unpredictable availability and shorter periods of concentrated effort. A task management system (such as GitHub Projects or Trello) that breaks down tasks into manageable chunks and provides necessary contexts can help them contribute without as much task-switching cost.

- Strategies for managing different geographies include virtual meetings, pulsed contributing times, and asynchronous editing of shared documents.

Affective trust is the belief (usually grounded in common experience) that group members have your best interests in mind. Some strategies for building it include:

- Spend social time together - meals, activities when in-person, but also, don’t skimp on icebreakers and check-ins when virtual

- Pay attention to mutual respect and speaking time. Explicitly acknowledge and credit new ideas as they come up.

- Be willing to look foolish. Ask the “dumb” questions that surface unquestioned assumptions. When some (leaders especially) make themselves vulnerable, it provides safety for others to do so.

- Consider assigning a vibes-keeper to track when the group becomes impatient, offended, or disengaged.

- Spend time early to talk through various perspectives on the question that may be present in the group.

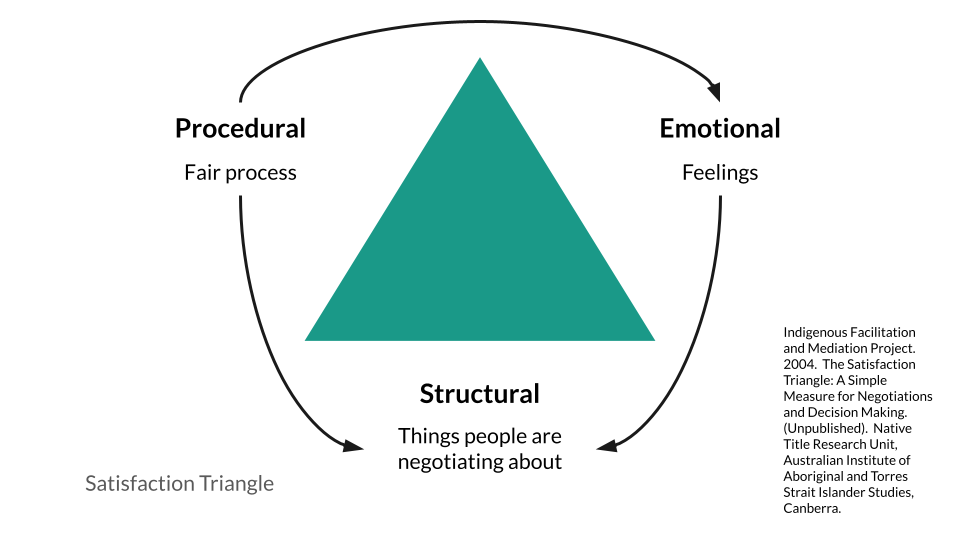

- Attend to conflicts as they arise.

All Contribute Some; None Contribute All