Communicating Findings

Overview

So you’ve done the research. Great! Now it’s time to get the word out. Science communication is the final step in the synthesis science process. It lets your work grow to be as impactful as it can be. But it’s hard, especially for those without training in it. In this module, we talk through some broadly applicable scicomm strategies that will get you started.

This module was designed to be highly interactive and includes a lot of peer editing. We highly recommend getting a small group of friends and or peers together so that peer editing and sharing can be a part of the experience!

Learning Objectives

After completing this module you will be able to:

- Define elements of (in)effective communication

- Identify relevant audiences for a particular work

- Identify jargon–when to use it, when to avoid it

- Translate communication into different formats

Preparation

None required.

Networking Session

Dr. Alex Phillips, Assistant Teaching Professor, Bren School of Environmental Science and Management, UC Santa Barbara

As a former NCEAS communications officer and a AAAS science and technology policy fellow in climate science, Alex brings extensive experience in making scientific synthesis engaging. Her teaching and research focuses on environmental communication to students, scientists, policymakers, and the public. She was also a postdoc at UCSB and the Large Lakes Observatory at University of Minnesota, Duluth where she investigated carbon sequestration in Lake Superior. She holds a PhD from Caltech in geochemistry, where she studied sulfur and carbon cycling in lakes and oceans.

Why Communicate Your Findings?

“Science speaks for itself.” “Good work will get recognized on its own.” “It’s the journal/university/lab’s job to share my results.”

All are common excuses that keep researchers from taking the initiative to communicate their science. But sharing your work is an essential part of maximizing it’s impact.

Some evidence (like this paper) shows that tweeting the results of a paper leads to more citations. Other studies disagree, but find that total engagement still increases when work is shared (from this paper). That engagement has rewards!

Putting your work out in public let’s others find it. That could lead to new collaborators, more citations, an article in the press, or even money from funders. If that work hides behind a paywall, it’s much harder for someone to find it!

Think about this–one SBC LTER researcher was walking on the beach, doing drone surveys. Someone stopped to chat, and they explained their research to them. A few weeks later, the SBC LTER had three million more dollars, after that person decided to donate to the cause. All from SciComm!

Today, we’re going to walk through turning your own research into an elevator pitch, a tight, concise explanation of what you’ve done. The process of creating an elevator pitch will give you the tools necessary to adapt your message to a variety of different audiences and formats.

Additional Resources

How Science Communication Can Boost Your Research - Alda Center

Crafting Your Elevator Pitch

This first exercise is a starting point. First of all, it’s really hard to distill your whole project down to a minute! Think about how much you left out, and how much it hurt to leave that out. From here, we’ll continue to refine and rebuild this elevator pitch.

The Power of a Story

Read the two following introductions to an essay about wildfire. Which essay would you rather continue to read?

Climate change is affecting all ecosystems. One of the impacts from climate change is that wildfire intensity is increasing across the globe, including in the Boreal Forest. Wildfire releases carbon into the atmosphere and threatens local communities. Some researchers are working on wildfire mitigation strategies in Alaska.

The smoke is thick in Fairbanks. Air the characteristic dirty orange of a nearby wildfire. Michelle Mack, lead PI of the Bonanza Creek LTER and long-time fire ecologist, saunters out of her lab. “It’s gone,” she says. Overnight, the nearby McDonald Fire burned one of her experiments down. The experiment explored an innovative approach to preventing wildfires. Now it was charcoal. (from Shaped by fire: the Bonanza Creek LTER)

What are the differences here? Version 2 has tension, which begs for a resolution–the reader has incentive to keep reading. The second has characters, which can inspire empathy. There is a tangible sense of time, a before, during, and after. The language in Version 2 is more dynamic, less technical.

Version 2 has the makings of a story–a narrative with a beginning, middle, and end. It has characters. It has scenes. Those, in combination, do a better job of engaging an audience than just facts do. Storytelling is a central part of communication. That should include science communication!

Ok–not every elevator pitch needs to start with “Once upon a time…” But thinking about building some sort of story into your elevator pitch can dramatically improve it’s effectiveness.

As someone who’s conducting the research, you already have stories. In fact, doing research is trying to figure out what a very specific story is–pulling a narrative from raw data. The trick to science communication is finding a different story, or modifying your story, to appeal to different audiences. We’ll cover that below.

Additional Resources

- A guide to scientific storytelling

- This is a great resource on the why of science storytelling.

- How to get an audience to care about your science | ‘Talking Science’ Course #4

- Great short video on hooking in a reader

‘And, But, Therefore’ Framework – A Storytelling Tool

The ‘And, But, Therefore’ (ABT) framework is a simple tool that helps develop a narrative in an elevator pitch (or any other short communication material). The temptation for many (researchers and non-researchers!) is to continue adding AND’s to their work.

Climate change is affecting all ecosystems. AND One of the impacts from climate change is that wildfire intensity is increasing across the globe, including in the Boreal Forest. AND Wildfire releases carbon into the atmosphere and threatens local communities.

But that doesn’t add up to any sort of great story, just a collection of facts. Scientific peers might know what to do with these facts (but…they still often don’t!), but most people don’t want to put in the effort to connect the dots.

The ‘And But Therefore’ framework provides a scaffolding from which to build a story.

This method really helps you focus in on just the critical parts of the story. There are many things that you’ll leave out. That’s more than OK–that’s the point! The first “and” is a setup–all your baseline information lives here. Let’s try this out with our Boreal forest research:

Spruce trees evolved to burn, AND as a result, wildfire is an important part of the Boreal forest ecosystem.

We’ve provided the bare minimum information for people to understand our research. But research addresses a problem. The “but” leads us to that problem:

BUT, climate change is making fires burn hotter and more frequently, and those fires are now beginning to threaten people who live near the Boreal forest.

Now, the audience knows the stakes, as well as the background. They want to know how that problem is being addressed! How will we protect those people that live near the Boreal?

THEREFORE lets you resolve the tension that was built by the BUT.

THEREFORE, researchers are designing fire mitigation strategies that protect these communities while simultaneously providing communities with spaces to farm or recreate.

All together, we get…

Spruce trees evolved to burn, AND as a result, wildfire is an important part of the boreal forest ecosystem. BUT, climate change is making fires burn hotter and more frequently, and those fires are now beginning to threaten people who live near the boreal forest. THEREFORE, researchers are designing fire mitigation strategies that protect these communities while simultaneously providing towns with spaces to farm or recreate.

Another example, on a completely different subject:

I’ll be using this paper as an example: Using a units ontology to annotate pre-existing metadata | Scientific Data

Scientific data needs units–meters per second, grams, etc.–to have any real meaning, AND researchers might write those units in any number of different ways, even though they refer to the same thing (e.g., “meters per second” might be written “m/s”, or “m-s”, or “m per s”). BUT computers read those different annotations as unique, preventing easy analysis across different datasets. THEREFORE an LTER working group developed a tool that turns a mess of units into a standardized unit ontology, solving problems with this method.

Additional Resources

- Randy Olson’s TED talk on the ABT framework (he’s the creator!)

- An expansion on ABT

- A great blog on ABT

Jargon

What is jargon? “Special words or expressions that are used by a particular profession or group and are difficult for others to understand,” as per the dictionary.

That’s not very useful. Let’s illustrate this better with an example:

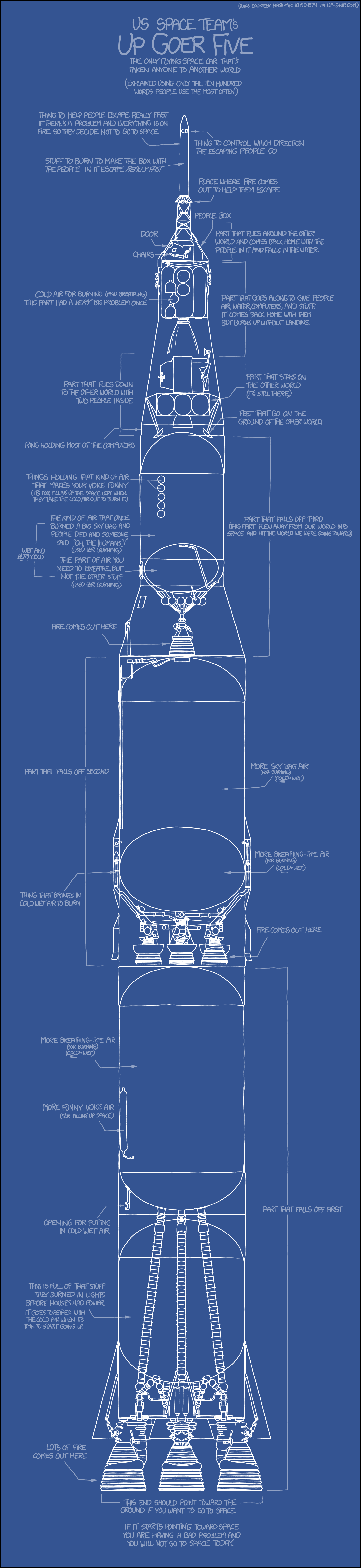

Click me!

This is a rocket, that’s described only by the thousand (ten hundred) most common words in English. Kind of a mess, huh!

Remember our elevator pitch for scientific data?

Scientific data needs units–meters per second, grams, etc.–to have any real meaning, AND researchers might write those units in any number of different ways, even though they refer to the same thing [“meters per second” might be written “m/s”, or “m-s”, or “m per s”]. BUT computers read those different annotations as unique, preventing easy analysis across different datasets. THEREFORE, an LTER working group developed a tool that turns a mess of units into a standardized unit ontology, solving problems with this method.

Numbers only mean something if they have a word at the end that tells us what they mean. But people that study how the world works write what they mean in different ways. Computers read those things they write to mean something wrong. So people that try and make life easier for the people that study the world came up with a way to make those the way people write what they mean the same. That way, the people that study the world can work together, using computers, and everyone understands.

Whew! Looks like we needed some…jargon to make this a bit better!

We All Need Jargon

Jargon is useful! Terms that refer to highly specific things streamline our ability to communicate. Too little jargon is also a problem!

Jargon is a shared language used by an “in-group.” Some of that jargon is shared by a large in-group–maybe environmentally-minded people. But for scientific jargon? Most people are not part of that group! That’s important for communicating science–you need to use terms that the audience understands. Remember, each audience might understand different terms!

But Russel Hirst, who has a great lesson on jargon, captured this important consideration nicely:

Remember, though: when you are reducing jargon, you must not damage accuracy. For example, if you were to substitute “burnable” for “flammable,” you could be doing readers a great disservice; “flammable” has a specific meaning. A flammable substance (such as gasoline) is not merely burnable; it is very easily ignited, will ignite if a flame or spark merely touches its fumes, and it burns with great intensity. - Russel Hirst

But Jargon is a Double-Edged Sword

So…use jargon but don’t use it wrong? Yep!

You’re going to have to use jargon. You might find that you have to use jargon that nobody but you and your labmates will understand. When this happens, it is critical that you define those terms! Explain what you mean early, and continue to remind the audience what you mean throughout your talk/video/casual chat.

But we don’t want clunky writing! One great blog post makes a key distinction between jargon and another type of unapproachable writing: “sentence fat”.

Sentence fat is unnecessarily clunky words and phrases that make it unreasonably hard to understand. When we remove these clunky phrases, our writing gets much more streamlined and easier to understand.

Let’s take a look at some good examples.

We calculated the volume of water in the adjoining ocean to assist local homeowners with maritime ecosystems as neighbors

Trimmed Version

We studied sea level to protect coastal communities.We present materials, mechanics, and integration schemes that afford scalable pathways to working arthropod-inspired cameras with nearly full hemispherical shapes.

Trimmed Version

New, high-tech digital cameras mimic bug eyes.This system works because of AI integration through motion scaling and tremor reduction.

Trimmed Version

This system works because of programming that makes the robot’s movements more precise and less shaky.Translate communication into various formats based on efficacy with target group

Trimmed Version

Adapt communication to fit different audiencesAdditional Resources

- [Explainer] Why do we use jargon when talking about science? - MongaBay

- How to explain a science idea clearly | ‘Talking Science’ Course #6 A really amazing video that goes far more in depth

Adapting Your Message to Different Audiences

You’re 17, back in high school. The football team had a party last night, and you and all your friends went. Describe the party to…

Your friend who was grounded and couldn’t go:

“It was crazy. Jackie did a kegstand!”

Your mom, who was hesitant to let you go:

“It was fun! Low key. Jackie was there–from soccer!”

Neither of these stories are false–but they’re narratives that are designed to best appeal to their target audience. Effective science communication does the same thing: it organizes its narrative around the ideas that best appeal to specific groups. Figuring out which story best appeals to specific audiences is the key to mastering effective science communication.

From Northeastern’s Tips for Effective SciComm:

Caution: who the heck is the “general public?”. Wants to know how your research impacts their lives and their societies. This communication could take the form of a formal presentation, or it could be a casual conversation with friends and neighbors.

Wants to know what makes the findings of your research important, including how it’s different from what others have done

Want to know whether your work will provide them with a significant return

Will be interested in determining whether your work may provide an opportunity for future collaboration, or how it ties into their own work

Need to know if a project has achieved the expected results and should progress to the next phase, or if changes are needed

Each of these audiences is looking for something different–they have different motivations and needs. You first need to understand what they’re looking for. Then, you can identify which stories will best address those needs.

Here are some things that differ between audiences:

- Knowledge of the issue

- How that issue affects them

- Values they hold

- What captures their attention

The first step is to try and understand the audience you’re writing for.

A funder familiar with the work won’t need you to tell them that climate change is a serious problem, but an eighth grader might! Or, if you’re posting a video on YouTube, you need to hook that audience in–finding something that’s interesting is paramount. That’s not as essential in a poster session or thesis defense!

Remember our elevator pitch? Thinking about audience should be second, after you identify your core story.

Note: “The general public” is not an audience! The public is not very general. Every subgroup has different motivations

Let’s try to adapt our example elevator pitch to two different audiences:

Spruce trees evolved to burn, AND as a result, wildfire is an important part of the boreal forest ecosystem. BUT, climate change is making fires burn hotter and more frequently, and those fires are now beginning to threaten people who live near the boreal forest. THEREFORE, researchers are designing fire mitigation strategies that protect these communities while simultaneously providing towns with spaces to farm or recreate.

A lot of people in Alaska are threatened by fire every summer, and instead of trying to put out every fire, they instead focus on stopping fires before they get to towns. They usually cut strips out of the forest around towns, but that’s kind of ugly and bad for the ecosystem. So instead, people are trying to figure out what they can do in those clear cuts! Some projects are growing berries, others put in aircraft landing strips or parks. Basically, if they’re going to cut those trees down anyways, it’s better to have some sort of useful space, rather than just empty land.

Fuel breaks are necessary for mitigating fire risk to local communities in Alaska. But fuel breaks are disruptive to the ecosystem, ugly to look at, and provide little to no value to local communities outside of mitigating fire risk. This project re-imagines fuel breaks to maximize benefits to local communities by providing space for parks, food production, or industry while maintaining their effectiveness as a fire mitigation strategy.

Additional Resources

- Good blog on understanding audience

- The message box–This is an oft reference tool for adapting scicomm to different audiences. I will warn that I find it unnecessarily confusing, and it’s nonlinearity sometimes tangles one’s ability to tell stories. But it’s here for your reference, because you will see it come up when researching scicomm.

- Adapted Creativities: How to customize your messages to win over different audiences–a good take on audience.

Where Do I Communicate?

Bluesky, Instagram, LinkedIn, Facebook, the university newspaper, lternet.edu, etc.–where does this stuff go?

First question: where do I already exist?

It’s easiest to share out with your own communities that you’ve built from the ground up.

Bluesky, Instagram, LinkedIn, Facebook, etc all offer low barriers to entry. Or, see if your site has a newsletter. I’m sure they’d love a story. Or, talk to your university (or research station!) press offices!

You are not alone! Social media is…social. When you post, make sure to tag other people and institutions that can get the word out. Write a piece for your university? Post about it! It’s always a good idea to acknowledge the LTER and NSF and other institutions in the work, anyways.

Communicating About Your Research…Before It’s Published

First of all, you all do this–talking to your advisor, a friend, etc. Here are some tips that might be useful when thinking about getting this out publicly. Why is it difficult to talk about early-stage research? Many of you have research that isn’t yet complete. But you can (and should!) be encouraged to share it share it!

Connecting With Your Press Office:

Tips from Harrison Tassoff, science writer for the UCSB Current.

- If you don’t tell us about it, we don’t know about it

- We want to share your work, and we want to get it right

- Don’t know whom to contact? Email someone that looks right. We can always direct you to the right person

- Not every paper/grant/award is news. But, if in doubt, email us

- Journalists can’t let you see a rough draft. Public Information Officers (those that work for the University, etc) generally will

- When you first contact a writer, please give us:

- A brief description of the research, what you found and why it matters (~1-2 paragraphs)

- The most recent version of the manuscript

- The journal name

- The embargo date and time (best guess is fine)

- What other institutions are involved and if they’re issuing a release

“Uh Oh, I Have an Interview With the Media”

- Five tips for scientists speaking to reporters. AAAS SciLine

- Science Communicators: How to Practice for a Media Interview. AAAS

- A Scientist’s Guide to Working with the Media. American Geophysical Union

Visual Storytelling

Other Resources

- NCEAS Learning Hub & Delta Stewardship Council. Open Science Synthesis: Communicating Your Science. 2023.